Introduction: The Invisible War in the Hangar

In every aircraft hangar from the massive Boeing assembly lines in Everett, Washington, to the humid MRO shops in Miami, Florida, there is an invisible war being fought every single shift.

On one side, you have Production. Their god is the Schedule. Their currency is “Turnaround Time” (TAT). They are driven by the intense economic pressure to get the aircraft out the door, back to the gate, and generating revenue for the airline.

On the other side, you have Quality. Their

god is the Standard. Their currency is “Airworthiness.” They are mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to ensure that every rivet, every wire, and every seal meets the rigorous specifications of the design data.

For the apprentice mechanic, the Quality Assurance (QA) department often feels like the “Department of No”—the guys in the white shirts who slow you down with paperwork and reject your work at 3:00 AM.

But as an expert with decades in the industry, I can tell you this: Production makes the money, but Quality keeps the license.

In this expert analysis, we will move beyond the basic textbooks. We will dissect the critical difference between Quality Control (QC) and Quality Assurance (QA), analyze the “Normalization of Deviance” that leads to disasters like the Boeing 737 MAX door plug, and explore why the “Inspector’s Stamp” is the most powerful—and dangerous—tool in the hangar.

1. Defining the Terms: QC vs. QA (The “Detective” vs. The “Architect”)

In the general world, “Quality” is a vague term. In the US aerospace sector, specifically under AS9100 Rev D standards, Quality is split into two distinct, warring disciplines. Confusing them is a rookie mistake.

Quality Control (QC): The Detective

QC is product-oriented. It is reactive. It happens after the work is done but before the product leaves the shop.

- The Action: An NDT technician using an Ultrasonic Probe to scan a wing spar for cracks is performing QC. A Line Inspector verifying the safety wire on an oil filter is performing QC.

- The Goal: To find a defect that already exists.

- The Analogy: QC is the police officer with a radar gun catching a speeding driver. The crime has already happened; now we have to deal with it.

Quality Assurance (QA): The Architect

QA is process-oriented. It is proactive. It looks at the system, not the hardware.

- The Action: An auditor reviewing the training records of the NDT technician to ensure they are qualified to use that probe is performing QA. A manager rewriting the tool calibration procedures to ensure torque wrenches are checked monthly is performing QA.

- The Goal: To prevent the defect from happening in the first place by designing a robust system.

- The Analogy: QA is the traffic engineer who designs the road with speed bumps and clear signs so that speeding is physically impossible.

Expert Insight: You cannot “inspect quality” into a product. If a part is manufactured poorly, no amount of NDT will fix it. QC finds the bad parts; QA fixes the system that made the bad parts.

2. The Regulatory Landscape: Part 21 vs. Part 145

To understand Quality in the US, you must understand which “Part” of the Federal Regulations (CFR) you are operating under. The mindset differs significantly.

Part 21: Manufacturing (Making the Plane)

This covers OEMs like Boeing, Cessna, or textron.

- The Focus: “Conformity.” Does this part match the engineering drawing exactly?

- The QA Challenge: Consistency. When you are building 50 planes a month, the challenge is ensuring Plane #50 is identical to Plane #1. The recent struggles at major OEMs have highlighted what happens when “Production Rate” pressure overrides “Conformity” checks.

Part 145: Repair Stations (Fixing the Plane)

This covers the MRO (Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul) world.

- The Focus: “Return to Service.” Is the aircraft airworthy according to the Maintenance Manual (AMM)?

- The QA Challenge: Variability. An MRO mechanic might work on a 20-year-old A320 today and a brand new B737 tomorrow. The variables are endless (corrosion, previous repairs, fatigue). The QA system here relies heavily on Required Inspection Items (RII)—critical tasks that require a second set of eyes (a “buy-back”) before the plane can fly.

3. The “Escaped Defect”: A Case Study on Documentation

In US aviation, the nightmare scenario is not a part that fails a test; it is a part that skips the test. We call this an “Escaped Defect.”

The Boeing Door Plug Incident (2024)

Context: In January 2024, an Alaska Airlines 737 MAX 9 lost a door plug in mid-air.

From a media perspective, it was a “loose bolt” issue. From a Quality Assurance perspective, it was a catastrophic failure of Chain of Custody. The NTSB investigation revealed that the bolts weren’t broken; they were missing. They had been removed to fix a rivet issue and never re-installed.

The Process Failure: The removal of the bolts was reportedly not documented in the official computer system (CMES). Because the removal wasn’t “open” in the system, there was no corresponding task to “close” it (re-install the bolts).

- The Lesson: This incident proved that physical work without digital documentation is lethal. In aviation, if it isn’t written down, it didn’t happen.

- The QA Fix: Modern QA systems are now implementing “forcing functions”—digital stops that prevent a job card from being closed until specific sub-tasks (like photographing the installed bolts) are uploaded to the server.

4. The Human Factor: “Pencil Whipping” and Normalization of Deviance

Technology breaks, but humans drift. The greatest enemy of Quality Assurance is not rust; it is psychology.

The “Pencil Whip”

Every mechanic in the US knows this slang. “Pencil Whipping” is the act of signing off a task in the logbook without actually performing it (or performing it fully).

- Example: A checklist says “Inspect all 50 rivets for tightness.” The mechanic checks 5, assumes the rest are fine, and signs the card “Satisfactory.”

The Normalization of Deviance

Coined by sociologist Diane Vaughan after the Challenger explosion, this concept explains why experienced mechanics make mistakes. It happens when people accept a lower standard of performance because “nothing bad happened last time.”

- Scenario: A mechanic borrows a torque wrench that is one day out of calibration. He uses it, and the plane flies fine. Next time, he uses one that is a week out. Then a month. Eventually, using bad tools becomes the “new normal” in the shop culture.

The QA Solution: SMS and “Just Culture” Historically, if a mechanic reported a mistake, they were fired. This encouraged hiding errors (and Pencil Whipping). Modern FAA-mandated Safety Management Systems (SMS) promote a “Just Culture.”

- The Deal: If you make an honest mistake and report it immediately (e.g., “I forgot to torque that bolt”), you are trained, not punished.

- The Exception: If you act with “Reckless Disregard” (intentionally violating a safety rule), you are terminated. QA is not about hunting witches; it’s about hunting broken processes.

5. The Economic Argument: The 1-10-100 Rule

For the MRO managers and investors reading this, Quality Assurance is often seen as a “Cost Center”—a department that spends money but generates none. This is a dangerous fallacy. The 1-10-100 Rule proves QA is an investment.

- $1 (Prevention): The cost to verify a process before work starts. (e.g., spending 1 hour training a mechanic on how to seal a fuel tank properly).

- $10 (Correction): The cost to catch a defect during QC. (e.g., The inspector finds the leak in the hangar. The sealant must be scraped off and reapplied. You lose material and labor hours).

- $100 (Failure): The cost if the defect escapes to the customer. (e.g., The plane leaks fuel at the gate in Chicago).

The Real Cost of the “$100” Scenario: When an aircraft goes AOG (Aircraft on Ground) due to a quality escape, the costs are astronomical:

- AOG Fees: $10,000 to $150,000 per hour depending on the aircraft and route.

- Passenger Compensation: Hotels, rebooking, vouchers.

- FAA Fines: Civil penalties can reach millions.

- Brand Damage: Ask Boeing how much a quality escape costs in stock value.

QA is the insurance policy against the $100 cost.

6. Root Cause Analysis: Beyond “Mechanic Error”

When a quality failure occurs, a lazy organization says: “Mechanic Error. Retrain the mechanic.” A world-class organization asks: “Why did the mechanic fail?”

In US aviation, we use Root Cause Analysis (RCA) tools like the “5 Whys” or the Fishbone Diagram.

Example Scenario: A batch of brackets cracked during installation.

- Why? Because the metal was too brittle.

- Why? Because the heat treatment was incorrect.

- Why? Because the oven thermostat was not calibrated.

- Why? Because the calibration vendor missed their schedule.

- Why? Because our Vendor Audit System failed to flag the expired certificate.

The Fix: You don’t just fire the guy who installed the bracket. You fix the Vendor Audit System. That is the difference between fixing a symptom and fixing the disease.

7. The Future: The Digital Thread & Augmented Reality

As we look toward 2026 and beyond, the clipboard and paper tag are dying. Aircraft MRO is becoming a digital ecosystem.

- Augmented Reality (AR) Inspection: Inspectors are beginning to use AR glasses (like HoloLens) that overlay the 3D Engineering Model onto the physical part. If a bracket is installed 2mm to the left, the glasses flash red. This removes the subjectivity of human visual inspection.

- Blockchain for Parts Traceability: To combat Suspected Unapproved Parts (SUPs), the industry is moving toward blockchain ledgers. This creates an immutable digital record of a turbine blade from the moment the metal is mined, through casting, to every repair it undergoes. A mechanic can scan a QR code and see the entire life history of the part, ensuring it is not a counterfeit.

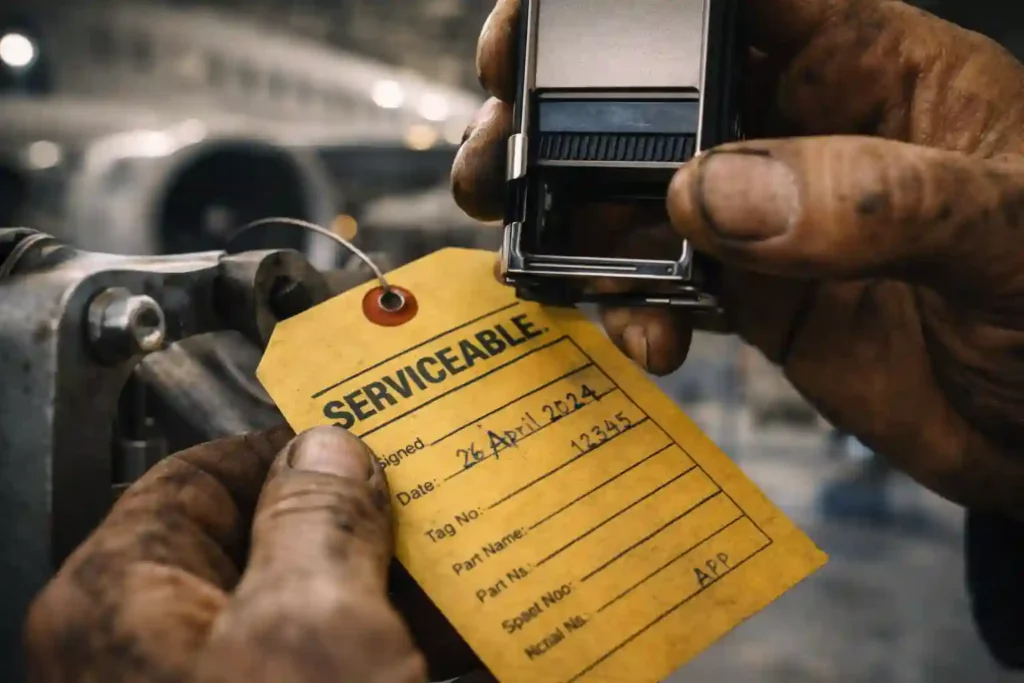

Conclusion: Protecting Your Stamp

To the aspiring technician or the veteran inspector reading this, I offer this advice: Protect your stamp.

In the US aviation system, your Inspection Authorization (IA), your Repairman Certificate, or your QC Stamp is a legal instrument. It is your bond. When you stamp a job card or sign an FAA Form 8130-3, you are testifying to the Federal Government—and to the passengers—that the work was done strictly according to the data.

Quality Assurance is not just a department on the second floor. It is a personal discipline. It is the courage to look at a torque wrench, see it is one day out of calibration, and put it back in the box, even if the foreman is screaming for the plane to leave.

In an industry defined by gravity, speed, and unforgiving physics, Quality is the only safety net we have.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the difference between AS9100 and ISO 9001? ISO 9001 is a general quality standard for all industries. AS9100 is the specific standard for the Aerospace industry. It includes all of ISO 9001 but adds nearly 100 additional requirements specific to aviation safety, counterfeit part prevention, and configuration management. You cannot build parts for Boeing or Airbus without AS9100 certification.

What is a “Bogus Part” (SUP)? In FAA terms, this is a Suspected Unapproved Part (SUP). It is a part that may look real but lacks the proper documentation (traceability) to prove it was manufactured or repaired by an authorized facility. QA departments exist to intercept these before they touch an aircraft.

What happens if a mechanic “Pencil Whips” a task? If caught, the consequences are severe. The mechanic can face immediate termination, revocation of their FAA A&P license, and in cases where fraud led to an accident, federal criminal charges and prison time.

What is an RII (Required Inspection Item)? An RII is a specific maintenance task that, if done incorrectly, could result in a catastrophic failure or loss of flight control. These tasks (like rigging flight controls or installing engine mounts) require a “double check” by a separate, authorized inspector. The mechanic cannot inspect their own work on an RII.

For more insights into the tools used to maintain quality, explore our Ultimate Aviation Mechanic Tools List.