Introduction: The “Billion-Dollar Pebble”

In the highly engineered world of aviation, where aircraft are designed to withstand lightning strikes and turbulent storms, the most persistent threat often comes from the most mundane sources. Foreign Object Debris, commonly known as FOD, refers to any object—live or inanimate—that is found in an inappropriate location within the airport or flight environment.

It can be as innocuous as a plastic coffee cup blown across the tarmac, or as dangerous as a wrench left inside a cowling by a mechanic. However, when this debris interacts with an aircraft, it transforms from “debris” into “Foreign Object Damage.” The consequences of this interaction are staggering. Industry analysis indicates that Foreign Object Debris costs the global aerospace sector over $13 billion annually in direct repair costs, flight delays, and aircraft changes.

As we navigate through 2025, the battle against FOD is evolving. Airlines and airports are moving beyond simple manual sweeping to deploy AI-driven radar systems and drone inspections. This comprehensive guide explores the physics of FOD, the tragic history that reshaped safety regulations, and the rigorous protocols that keep our runways safe.

The Economics of Debris: A Hidden Tax

For the average passenger, a flight delay is a nuisance. For an airline, a delay caused by Foreign Object Debris is a financial hemorrhage. The cost of FOD is often described as the aviation industry’s “hidden tax.”

Direct vs. Indirect Costs

- Direct Costs: These are the visible bills. If an engine ingests a flock of birds or a loose screw, the airline must pay for the engine tear-down, the replacement of titanium fan blades, and the labor hours required for the repair. A single damaged fan blade on a modern engine like the GE9X can cost upwards of $50,000 to replace.

- Indirect Costs: These are often 10 times higher than the direct costs. When an aircraft is grounded due to Foreign Object Debris, the airline faces:

- Flight cancellations and passenger compensation (EU261 claims).

- Crew scheduling disruptions.

- Loss of brand reputation.

- The immense logistical cost of sourcing a replacement aircraft.

To mitigate these risks, major carriers invest heavily in Aircraft MRO (Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul) capabilities to ensure that if damage occurs, the aircraft can be returned to service as quickly as possible.

The Three Categories of FOD

Foreign Object Debris is not a monolithic enemy. It originates from three distinct environments, each requiring unique prevention strategies.

1. Runway and Apron Debris (External)

This is the most common form of FOD found at airports. The vast expanses of concrete and asphalt are magnets for loose items.

- Inorganic Debris: This includes luggage tags, zipper pulls, soda cans, and chunks of asphalt breaking loose from aging runways.

- Aircraft Parts: It is not uncommon for aircraft to shed parts. Fuel caps, tire fragments from landing gear, and rivets can vibrate loose during takeoff and landing.

- Weather Hazards: Hail and ice are naturally occurring Foreign Object Debris. Large hailstones can shatter windshields and dent leading edges, while ice shedding from wings can be ingested into rear-mounted engines.

2. Maintenance FOD (Internal)

This is the most insidious form of debris because it is often invisible until it is too late. It occurs when items are left inside the aircraft during maintenance.

- The “Lost Tool” Syndrome: A mechanic leaves a flashlight or a pair of pliers inside a fuel tank or behind a flight deck panel. As the aircraft vibrates in flight, this tool can chafe against hydraulic lines or short-circuit electrical bundles.

- Consumables: Safety wire clippings (snips of metal wire used to secure bolts) are a major hazard. If not swept up, they can jam sensitive flight control pulleys.

- Prevention: This is why the role of the Aviation Maintenance Technician is so disciplined. Strict “Tool Control” policies ensure that every item taken onto an aircraft is accounted for before the access panels are closed.

3. Wildlife Hazards (Biological FOD)

Birds and terrestrial animals pose a significant threat. A 12-pound Canada Goose striking an aircraft at 150 knots delivers an impact force equivalent to a heavy artillery shell.

- The Miracle on the Hudson: The most famous example of wildlife Foreign Object Debris was US Airways Flight 1549. A bird strike destroyed both engines, forcing Captain Sully Sullenberger to ditch in the Hudson River.

- Mitigation: Airports use “Bird Control Units” equipped with pyrotechnics, lasers, and even trained falcons to keep airspace clear.

The Concorde Lesson: A Tragic Case Study

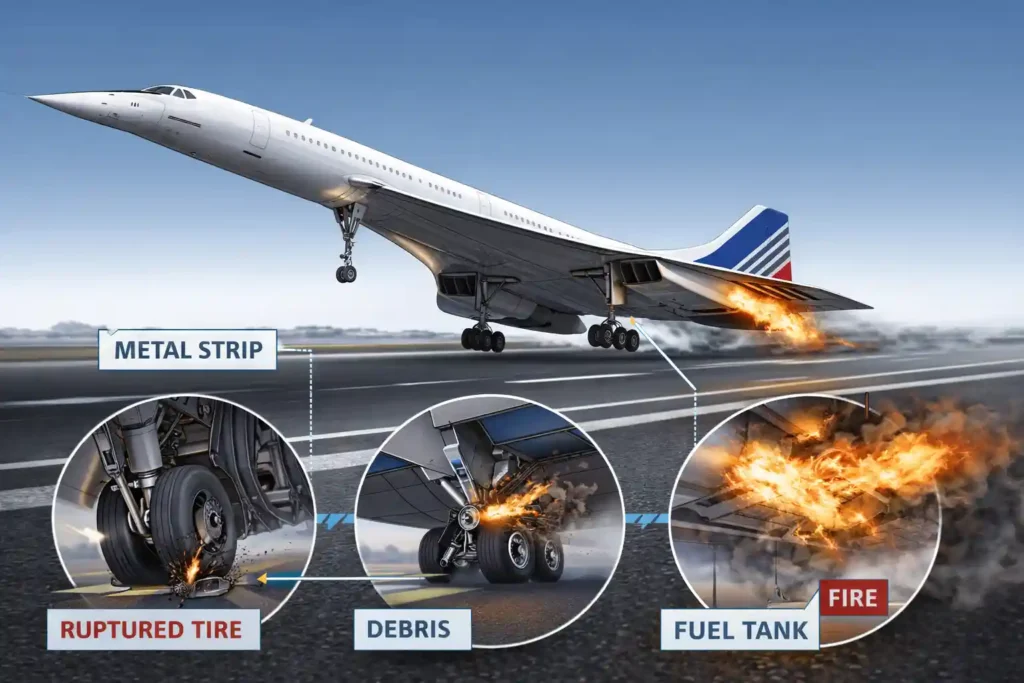

The danger of Foreign Object Debris was tragically immortalized on July 25, 2000. Air France Flight 4590, a supersonic Concorde, crashed moments after takeoff from Paris Charles de Gaulle, killing all 109 people on board and 4 on the ground.

The investigation, led by the BEA, revealed that the crash was not caused by a flaw in the Concorde itself, nor by pilot error. It was caused by a piece of Foreign Object Debris left on the runway by a Continental Airlines DC-10 that had departed just minutes earlier.

The debris was a small titanium wear strip, roughly 43 centimeters (17 inches) long. When the Concorde ran over it at high speed, the strip slashed the tire. A massive chunk of rubber, weighing 4.5 kilograms, was thrown upward into the underside of the wing. This impact created a shockwave that ruptured fuel tank #5, igniting a catastrophic fire. This disaster serves as a permanent, somber reminder that in aviation, “small” debris does not mean “small” risk. It reshaped global regulations on runway inspections and tire durability.

Detection Technology: The Eyes of the future

While the human eye is a powerful tool, it is fallible, especially at night or in bad weather. To combat this, the aviation industry has turned to advanced technology to detect Foreign Object Debris.

1. Millimeter-Wave Radar

Major international hubs like Heathrow, Dubai, and JFK are deploying automated FOD detection systems (such as the Trex or Xsight systems). These systems place millimeter-wave radar sensors along the length of the runway. They scan the surface continuously, 24 hours a day.

- How it works: If an object as small as a rivet lands on the tarmac, the radar detects the anomaly. AI software analyzes the return to differentiate between a rock, a bird, or a piece of metal.

- The Response: The system alerts the Air Traffic Control tower and provides GPS coordinates. Operations vehicles are dispatched to retrieve the object immediately.

2. High-Resolution Optical Scanning

Hybrid systems combine radar with high-definition optical cameras. When the radar detects a target, the camera zooms in to provide a visual confirmation. This reduces “false alarms” caused by things like tall grass or insects, ensuring that runway closures only happen when necessary.

3. Drone Inspections

By 2026, autonomous drones are becoming a standard tool for apron inspections. Before a peak wave of departures, a drone can fly a pre-programmed path over the taxiways, using computer vision to map potential Foreign Object Debris and alert ground crews.

Prevention Protocols: The “Clean As You Go” Culture

Technology helps, but the first line of defense is culture. Preventing Foreign Object Debris requires a mindset shift where safety is everyone’s responsibility, from the CEO to the baggage handler.

The “FOD Walk”

This is a ritual at military airbases and commercial MROs alike. Before the start of flight operations, a line of personnel stretches shoulder-to-shoulder across the tarmac. They walk slowly, heads down, scanning the ground. Every pebble, wire, or piece of plastic is picked up and placed in a designated pouch. It is a simple, low-tech solution that remains surprisingly effective.

Shadow Boards and Tool Control

In the hangar, accountability is absolute. Aviation mechanics use “shadow boards”—foam-lined toolboxes where every wrench, socket, and screwdriver has a specific cutout.

- The Rule: If you finish a repair and a slot in your toolbox is empty, the aircraft is grounded. No exceptions.

- RFID Tracking: Modern tools are embedded with RFID chips. If a tool is missing, scanners can detect if it is hiding inside the aircraft fuselage, saving hours of searching.

Internal Engine Inspection

When ingestion is suspected, guessing is not an option. Technicians employ advanced Borescope Inspection techniques to snake flexible cameras deep into the engine core. They look for “nicks and dings” on the leading edges of compressor blades—the tell-tale forensic signs that Foreign Object Debris has passed through the engine.

Reporting and The “Just Culture”

One of the most critical aspects of FOD prevention is the reporting system. In the past, mechanics might have been afraid to report a lost tool for fear of being fired. Today, the industry operates under a “Just Culture.”

As promoted by organizations like the Flight Safety Foundation, a Just Culture encourages honest reporting. If a technician accidentally drops a washer and can’t find it, they are encouraged to report it immediately so it can be retrieved. They are not punished for the honest mistake; they are only punished if they hide it.

This data is often shared globally through systems like the NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS), allowing airlines to learn from each other’s incidents without fear of legal reprisal.

Conclusion

Foreign Object Debris remains a constant, asymmetric threat to aviation safety. It is a war fought on two fronts: the macroscopic world of runway management and the microscopic world of engine maintenance.

For airlines, the investment in prevention—from automated radar systems to strict tool control protocols—is minuscule compared to the catastrophic cost of a single incident. The safety of the skies relies on a continuous, vigilant partnership between advanced technology and the disciplined professionals who maintain the fleet. By treating every loose bolt as a potential disaster, the industry ensures that the only thing taking to the skies is the aircraft itself.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the most common source of Foreign Object Debris? While it varies by airport, “apron trash” is the most frequent offender. This includes personal items dropped by ground crews, luggage tags, plastic shrink wrap from cargo pallets, and loose gravel from degrading pavement.

2. Can a small coin really damage a jet engine? Yes. Modern jet engines operate at incredibly high rotational speeds. A coin sucked into the intake acts like a bullet. It can dent a compressor blade, disrupting the airflow and causing a compressor stall, or worse, shatter a blade which then destroys the engine from the inside out.

3. How do pilots know if they hit FOD? Pilots may hear a loud bang or feel a vibration. In the cockpit, they might see engine parameters (EGT or N1 vibration) spike. However, minor FOD damage is often not noticed until the post-flight inspection performed by line maintenance crews.

4. Who pays for FOD damage? If the debris is traced to a specific source (e.g., a tool left by a third-party maintenance provider), the airline can sue for damages. However, for general runway debris, the airline usually absorbs the cost or claims it through insurance, causing premiums to rise.

5. How often are runways swept? International standards (ICAO) require daily inspections. However, busy airports typically perform visual inspections multiple times a day and use “FOD Boss” friction mats or vacuum sweeper trucks to continuously clean the movement areas.