The first time I drew a polar arc that shaved an hour off the schedule, I remember the room going silent when the dispatcher asked, “Do we really need EDTO 330 for this, or can we keep it inside 240?” We had a gorgeous great-circle, but an alternate went amber, surface temps were pushing fuel-freeze margins, and the OEI ring nicked 186 minutes. We either re-routed through Greenland and burned the savings—or leaned on a higher EDTO. That’s the reality: you don’t “need” 240–370 just because a route looks polar. You need it when your worst-case OEI diversion time and time-limited systems say so—and when winter or NOTAM roulette makes alternates fickle.

Below is the field guide I wish I’d had earlier in my career—plain-English, story-tested, and geared for flight ops managers, dispatchers, and pilots who have to sign for this stuff.

First principles (in human speak)

ETOPS (FAA) governs extended operations for twins beyond 60 minutes from an adequate airport (and, for passenger multiengine airplanes, beyond 180 minutes). It’s a U.S. framework that also contains a dedicated Polar Operations chapter. If you want the regulatory definition of the polar areas in one click, it’s right here: 14 CFR §121.7.

EDTO (ICAO/EASA) is the international, aircraft-agnostic lens—“Extended Diversion Time Operations”—that focuses on maximum diversion time and time-limited systems (cargo fire suppression, oxygen, etc.). Same physics, slightly different vocabulary.

Polar ≠ automatic “beyond 240.” Plenty of trans-Arctic tracks can be flown at ETOPS/EDTO-180 if you stick to Alaska–Greenland–Iceland corridors and the alternates behave. The catch is weather and service variability: when one rung in your ladder goes red, do you still have a legal arc? That’s where 240 (and sometimes 330/370) earns its keep.

What actually gates your approval level

I’ve seen smart teams get tripped up by headlines. Ignore them. Your required approval is set by the longest, worst-case OEI diversion time between adequate alternates along your proposed track, computed with your approved OEI cruise speed and dispatch assumptions (winds/temps, MEL/CDL). Then check whether any time-limited systems (most famously, cargo fire suppression) cap you below that number. If your max computed diversion is ≤180 and your alternates are credible, you don’t need more. If it pokes past 180, you’re into 240+ territory.

From experience: the EDTO critical fuel calculation at the most critical point is where rosy assumptions go to die. Run it cold, with headwinds and realistic icing/anti-ice penalties, before you promise a route.

What the fleet can do today (and what ops must still earn)

- Boeing 787 type design carries FAA ETOPS-330; plenty of operators use that to keep efficient arcs open when alternates are sparse. See Boeing’s announcement for context: FAA Approves 330-minute ETOPS for 787.

- Airbus A350-900 was the first airliner approved up to 370 minutes before EIS—enough to span essentially any polar arc where alternates are usable. EASA’s notice has the details: A350 ETOPS up to 370 minutes.

Important nuance: type-design capability ≠ operator approval. Your airline still needs the matching OpSpecs/EDTO/ETOPS authorization, reliability history, and city-pair risk work to use it.

So… do you need 180, 240, 330, or 370?

When 180 is enough:

You’re threading a chain of robust alternates (Greenland/Iceland corridor), winter ops are tame, and you’re willing to bend the track to stay “inside the circles.” You’ll trade a few minutes of block for avoiding higher EDTO—and accept less resilience if a field suddenly drops out.

When 240 is the sweet spot:

You want more direct arcs where alternates are thin, winter is winter, and runway conditions, RFFS category, de-ice, or fuel availability can go sideways. EDTO/ETOPS-240 usually buys the routing you actually want and reduces late re-plans.

When 330–370 unlocks everything:

You’re routinely drawing deep-polar tracks or facing geopolitical constraints that lengthen the hops between adequate alternates. 330 bridges the last big gaps across the high Arctic; 370 (think A350) gives near-global freedom to pick fuel-optimal winds while staying compliant—even on days when your favorite alternate is snow-packed or NOTAM-hamstrung.

The “extra” layer: U.S. FAA Polar Ops requirements

Even with ETOPS/EDTO in hand, once your route touches the North Polar Area (≥78°N) or South Polar Area (≤60°S), you need Polar Operations authorization and procedures: cold-fuel management and fuel-freeze margins, HF/SATCOM comms, space-weather/solar radiation plans, special equipment (yes, anti-exposure suits—typically at least two), and—this one’s easy to overlook—a practicable passenger recovery plan for your designated polar alternates. FAA guidance spells out the package and how it’s validated; I still keep AC 120-42B (ETOPS) on my desktop because it ties the extended-ops logic together cleanly: FAA AC 120-42B (ETOPS).

Also worth bookmarking for quick definitions and cross-checks: 14 CFR §121.7 (North/South Polar areas).

A fictional—but realistic—case study from a winter dispatch

City pair: Chicago–Osaka, 787-9

Plan A: A clean polar arc that skimmed 182–188 minutes OEI between two preferred alternates; both had decent RFFS and fuel.

Complication: One alternate NOTAM’d limited de-ice and a plow schedule; the other was open but marginal crosswinds.

Crunch: Our OEI time at the most critical point ticked up to 191 minutes with headwinds, and the cargo fire-bottle endurance left us zero margin if we iced up on the divert.

What we did: We re-worked to an EDTO-240 plan (within our OpSpecs) and picked a more westerly arc that kept two credible alternates inside 210 minutes even if one degraded. We added cold-fuel monitoring callouts (SAT margins, fuel-freeze point on the release) and filed the Polar Ops kit checklist.

Takeaway: We didn’t “need” 330 to fly that day, but 240 made the plan survivable when the alternates were twitchy—and saved a last-minute zigzag that would’ve burned the fuel we were trying to save.

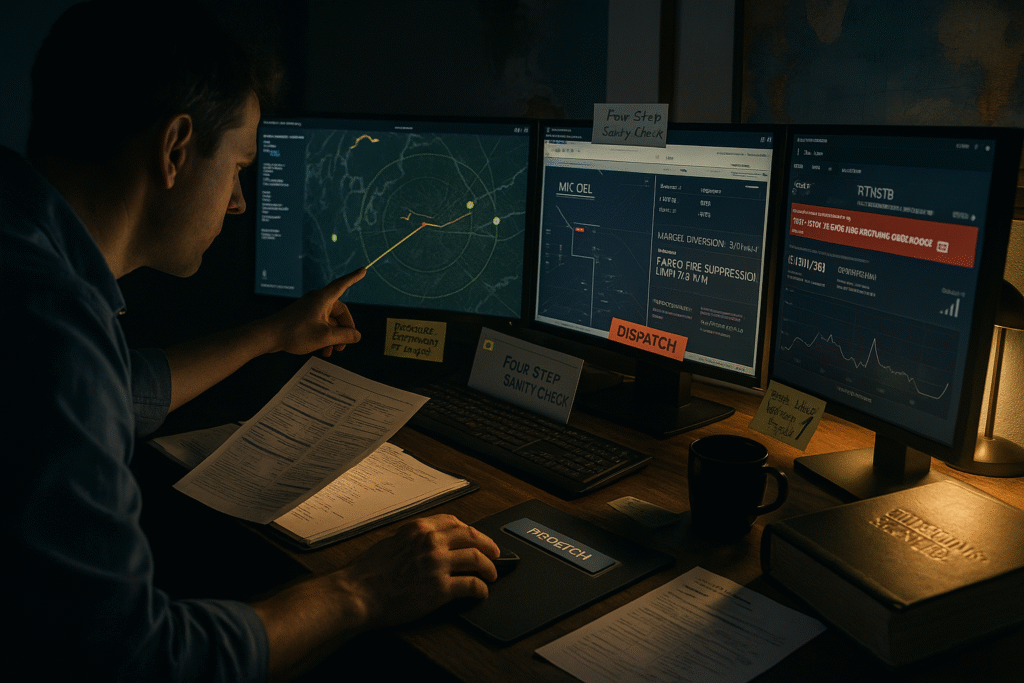

How I make the go/no-go call on approval levels (my four-step sanity check)

- Map your track and alternates. Apply company minima and remove airports with legal or practical restrictions (emergency-use only, no customs when you need it, night closures, no handling).

- Compute the max OEI diversion time. Use the approved OEI cruise and conservative winds/temps. Now overlay time-limited systems; the shorter number rules.

- Stress-test availability. Pull seasonal weather stats, review NOTAM volatility, and sanity-check services (de-ice, RFFS, fuel). If one alternate drops, can you still live inside 180?

- Pick the authority that matches your network risk. If your plan survives at 180, great. If it dies every time a snowplow sleeps in, bite the bullet and get 240 (or 330/370 if your routes routinely stretch the lattice).

For a running digest of regulatory changes that can nudge these decisions, we track highlights in Regulatory Updates, and we keep a market-context view in Industry News & Market Trends.

Don’t forget the human factors and “cold” realities

- Fuel freeze & SAT margins. I’ve seen crews treat fuel freeze like a footnote. It isn’t. Cold-fuel procedures (monitoring temperatures vs. freeze point, step-climb logic, and turn-back triggers) belong in the release and briefing, not just the manual.

- Space weather. On the rare days solar activity spikes, HF behaves badly and dose management matters. Your polar checklist should include space-weather sources and reroute triggers.

- Comms redundancy. HF and SATCOM both have their bad-hair days. Don’t let a single-channel MEL box you into a corner at high latitudes.

- Passenger recovery. A polar alternate without a warm bus or a plan is a PR disaster. Work the on-ground scenario with the station long before the FAA asks you to prove it.

Quick answers I get from chief pilots and dispatch leads

“Is 370 mandatory for polar?” No. It’s rarely “required”—it’s strategic headroom. Many arcs are fine at 180–240; 330–370 expands options and resilience.

“Do modern twins really hold these approvals?” Yes. The 787 carries ETOPS-330 (type design), and A350-900 has approval up to 370 minutes—your OpSpecs must match before you can use them (Boeing 787 ETOPS-330; EASA A350 370-minute).

“Where do I find the U.S. polar definitions and the extended-ops rule DNA?” Start with 14 CFR §121.7 and the FAA’s extended-ops circular AC 120-42B.

“Who else has a clean explainer on the operator side?” Airbus and Boeing both publish polar-ops notes. For a neutral primer that bridges tech and ops, our Aircraft Models & Reviews section links type-specific ETOPS/EDTO capabilities to real route choices.

Final takeaways you can brief today

- You need what your route needs. If your worst-case OEI diversion fits inside 180 with credible alternates, you don’t need more.

- EDTO/ETOPS-240 is the modern sweet spot for operational flexibility and weather resilience on most polar-adjacent routes.

- 330–370 is the “draw anything, survive surprises” tier—especially handy when alternates or airspace access change on short notice.

- Polar Ops authorization is additive. Even with extended-ops authority, U.S. operators still need the polar kit: cold-fuel, comms, radiation procedures, anti-exposure suits, and a recovery plan—validated with the FAA (AC 120-42B).

I got what you intend, thanks for posting.Woh I am delighted to find this website through google. “Do not be too timid and squeamish about your actions. All life is an experiment.” by Ralph Waldo Emerson.