Ask any line captain and they’ll tell you: smooth, routine legs are won during planning; tough flights are won in seconds. When the radar blossoms red, an engine starts “whispering,” or granite gets close, the difference between an incident and a non-event comes down to habits you built long before pushback. This guide humanizes those moments and shows how pros decide—quickly, safely, repeatably—using a simple spine: aviate → navigate → communicate. I’ll weave in real cockpit texture, a fictionalized (but technically faithful) case study, and the crisp phraseology that keeps crews together under pressure.

If you want deeper drills, I’ll point you to the material the pros actually use: the FAA Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge for core judgment and human factors, the AIM for phraseology that plays well with ATC, the Aviation Weather Center for preflight weather that doesn’t lie to you, and NASA ASRS for lessons paid for by other people’s gray hair. Those four links, plus your company SOP, are how you turn “hope” into a brief you can fly.

The mental model pros really use

Every story in this piece rests on one unbreakable flow:

- Aviate — Set the attitude and power that make the airplane behave. Known pitch–power numbers and mode awareness mean you never bargain with airspeed or angle of attack.

- Navigate — Put safe air under you: lateral clearance, vertical clearance, energy and escape routes. Terrain, weather, fuel, and performance—always in that order.

- Communicate — Tell the people who can help (ATC), the people you’re responsible for (cabin, pax), and the box (FMS/automation) what you’re doing, not what you’re thinking about maybe doing.

That order is non-negotiable. The FAA PHAK and AIM are explicit about it, and every good airline SOP echoes the same.

Weather: when the sky throws a surprise

Scenario: Descent into a busy hub. You planned for “vicinity showers,” but the returns just hatched into a convective line with outflow boundaries. Ride changed from polite chop to “secure the galley.” You’ve got cells painted 20° left of course and a build on final.

How pros play it:

- Aviate: Set turbulence penetration speed and stop “chasing” altitude if the autopilot hunts. If the airplane has a good “turb” mode, use it; if not, hand-fly with a target pitch and power, ride the bumps, and trim. Belts on. Call it.

- Navigate: Offset early—20–30° buys you working room. Respect anvil outflow; don’t scud-run under an overhang. Put a hold or divert on the table before ATC offers. Strategic avoidance beats “threading the needle” 100 times out of 100.

- Communicate: “Center, unable present heading due weather, request 30 right for deviation.” With the cabin: “We’re deviating for weather; it’ll be bumpy for 10–15 minutes. Crew secure.” Calm, short, specific.

From my logbook: I’ve “saved” more days with a 12-minute hold and a legal alternate than with any hero move through a gap. When the Aviation Weather Center outlook whispers “organized convection,” I brief a no-go box on the approach plate and give my FO the latitude to say, “Let’s try the other side.” Best go-around of my year? The one I called before we scraped into the approach gate with a boiling cell parked on final.

Micro-playbook for crews

- Draw a weather line in the briefing (“no reds within 20 NM of final”).

- Speed is life in bumps; don’t trade energy for altitude vanity.

- Keep an “out” warm (the upwind ILS, the 15-minute hold, or the inland alternate).

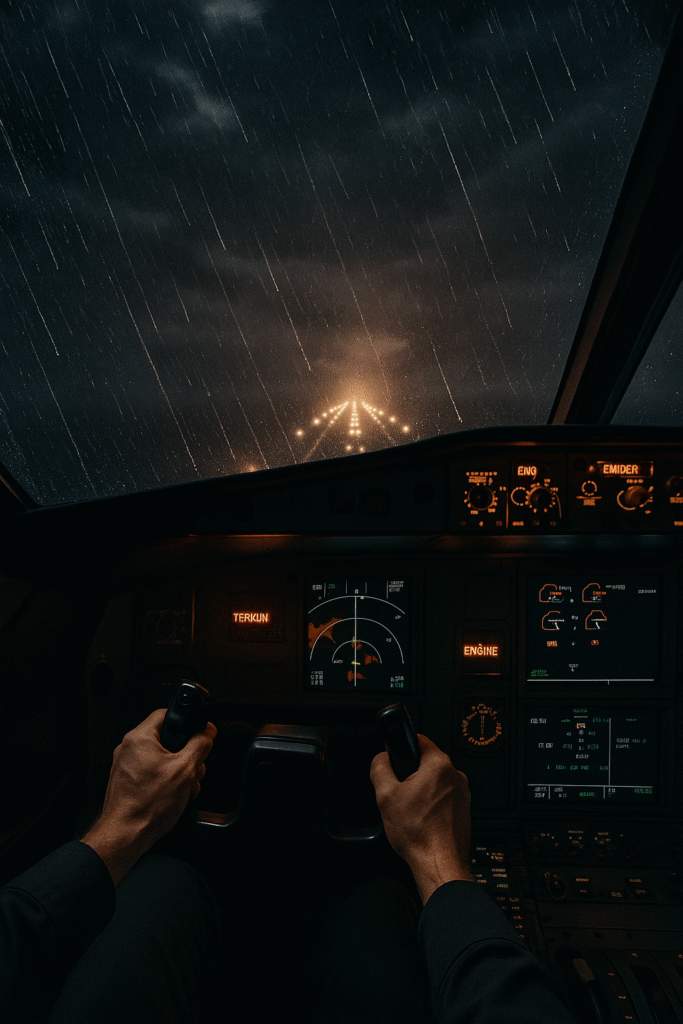

- If it turns into a rain-on-glass night? Fast wipers, lights down, “aim small” on PAPI.

Want to see how crews frame weather in real time? Read a handful of rain-soaked narratives in NASA ASRS and you’ll see the same pattern: simple calls, honest limits, energy protection.

Engines: detect small lies before they become big truths

Engines rarely fail like the movies. They whisper first: a lazy spool, a rising EGT split, oil temp that’s a hair north of “normal,” a vibration nibbling at the needle. Instrument literacy is how you catch hints without fixating.

The tempo that keeps you safe:

- Stabilize the flight path. Pitch, power, trim. Guard speed and AoA; the airplane doesn’t care about your hunch until it’s stable.

- Diagnose deliberately. “Which side is sick?” Call the cue (“EGT split right 60°”), cross-check (N1, N2, FF, vib, oil), and use standard callouts to avoid the wrong-lever boogeyman.

- Memory items (if applicable), then QRH. Don’t freelance your way past the checklist.

- Plan the path. Terrain, weather, fuel, driftdown/engine-out grad, nearest suitable runway. “Home field” isn’t always suitable today.

From my experience: The best engine calls are boring. On a winter transcon last year, we saw a left-engine vib rise from 0.7 to 1.7 with a mild rumble. Everything else was green. We leveled, brought the throttle back a notch, stabilized the needle, got the QRH out, and turned early toward a VMC field with long concrete and full support. Total extra block time: 40 minutes. Pax thought it was weather. That’s a win.

Cruise driftdown sanity check (two-engine class):

- Set MCT, level if needed, green dot/EO speed, bug the MORA/MEA.

- Execute driftdown or engine-out profile per QRH; consider oxygen/pack configs.

- ATC: “Mayday/declaring engine failure, unable maintain FLxxx, driftdown, request block altitude and direct [safe fix].”

If you want to study the arc of these events without armchair quarterbacking, the NTSB dockets are great—but for daily pattern recognition, again, ASRS is gold.

Terrain: CFIT is allergic to honesty

Controlled flight into terrain doesn’t happen because pilots can’t fly; it happens when pressure, pride, and poor picture beat the brief. At night, in marginal weather, near mountains, you need a hair-trigger for the bigger picture: terrain rings, MSA/MORA, MEA’s that climb faster than you can.

Three rules that save lives:

- Ring discipline. Keep the 5/10/20 NM terrain rings up in the map. If your lateral plan puts red under the nose, it’s not a plan.

- Unstable = go-around. If you’re late to the approach gate, chasing a descent with speed and path off, call it. No speech. “Go-around, flaps ___.”

- Respect the box. When EGPWS/TAWS says “TERRAIN AHEAD, PULL UP,” you don’t audit the computer—you pitch, power, roll, then ask questions.

Mountain playbook:

- Arrivals with step-downs? Brief the vertical path as if the VNAV will drop out.

- Strong winds aloft? Expect mountain wave downslope. Add energy margin and don’t promise a slam-dunk.

- Visual illusions at night? Use VASI/PAPI and odd-even DME gates; avoid “black-hole” descents over sparsely lit valleys.

A (fictional but faithful) case study: “The Ridge, The Rumble, and The Reroute”

Flight: 321NM regional leg, winter evening, turbojet.

Weather: Ceiling 1,700 OVC, 4 SM light rain, gusty 220/25G35, freezing levels 5,000–7,000, ragged line on final approach course.

Terrain: Rolling hills with a 4,300’ ridge 18 NM southwest of the field.

T-20 minutes: We see a “fresh” cell pop right on final. I brief: “No-go box: red returns within 15 NM of final. Out: RNAV on the cross runway upwind side, or hold SE of the ridge at 6,000 until it washes.”

T-12: Ride gets sporty; FO calls a left-engine vibration spike from 0.4 → 1.5 with a faint hum. EGT, N1, N2 normal.

Aviate: We set turb speed, autopilot in a stable mode; I say, “My aircraft.”

Diagnose: FO: “Vib left 1.5; other parameters green.” We try a one-click power reduction. Vib drops to 1.2; hum subsides.

Navigate: The cell on final grows teeth. We request 30° right for weather. Approach offers a shortcut back to the ILS. I say, “Negative, request RNAV 22 upwind side or hold southeast.”

Communicate: “Approach, due weather and a minor engine vibration we’re managing, request RNAV 22 and long final or holding SE.”

Outcome: We shoot the RNAV 22 with a 12-mile straight-in, winds 220/22G32 3/4 down the runway, and roll gently with a crosswind technique we beat to death in the sim. Taxi in uneventfully. Maintenance finds a slightly out-of-balance fan blade; weather washed the original final 10 minutes after our go-around would’ve happened. Nobody on board knows how close this got to “spicy.”

What mattered: We protected the airplane (energy), protected ourselves (terrain/ weather margin), and didn’t accept an approach that violated our own no-go box. And we said exactly what we needed on the radio, once.

Words that work when seconds count

Borrow these and make them your crew’s muscle memory:

- Weather: “Unable present heading due weather, request 30 right.” “Request hold southeast at 6,000, expect further in 10.”

- Engine issue (non-memory): “We have a parameter anomaly; no memory items. We’ll stabilize, QRH to follow.”

- Terrain/unstable: “Go-around, flaps ___.” (Say it at the gate—1,000’ IMC/500’ VMC stable call—without apology.)

- Priority fuel: “Minimum fuel” (you’re not in distress yet, but you can’t accept undue delay). If the math turns ugly: “Mayday fuel.”

- Cabin: “We’re deviating for weather; expect 10–15 minutes of bumps. Crew secure.” Clear, short, human.

Build habits before you need them

You don’t “find” discipline at 1,000’ in the rain—you bring it. This is the weekly practice that pays off when minutes get tough:

- Chair-fly your approach brief with a no-go box and a named “out.”

- Keep a one-liner “engine-out at cruise” script on your knee card (driftdown, oxygen, safe fix).

- In the sim, ask for nasty winds and terrain-pinned go-arounds. The first time you hear “TERRAIN AHEAD” shouldn’t be in real terrain.

- After a day with genuine bumps, spend 10 minutes in NASA ASRS reading someone else’s near-miss. The pattern recognition is free.

For structured drills you can copy into your next study block, start with our Flight School Guides and layer in targeted scenarios from Simulator Technology. If you’re debriefing a headline incident with your crew, our Safety Incidents & Investigations hub pulls together the nuts-and-bolts takeaways without the speculation.

Quick, high-value checklists you’ll actually use

Thunder day descent

- Penetration speed set, belts on, “Crew secure” call

- 20–30° lateral offset early

- No-go box hot; upwind alternate named

- Cabin brief: 15 minutes of bumps, carts stowed

Engine “whisper” at cruise

- Pitch/power/trim; stop the drift

- Cross-check parameters, “Which side is sick?”

- No memory items? Open QRH; don’t rush

- Driftdown/engine-out path: terrain, oxygen, safe fix, ATC call

Night, terrain, marginal

- Terrain rings up, MSA/MORA in the bug

- Unstable at gate? Go-around—no debate

- Treat “PULL UP” as action, not a suggestion

Personal pitfalls I still brief out loud

- Automation temptation. VNAV/LNAV are great—until they aren’t. If the airplane chases a path through gusts, go basic: pitch–power and a level segment.

- Press-on bias. “We can squeak this in.” That sentence lives in a lot of reports you don’t want your name on. If you’re late to stable, you’re early to the go-around.

- Map zoom lies. If the tactical display is on 5 NM and everything looks fine, zoom to 20. Red that was “over there” might be right there.

Preflight: the 7-minute brief that pays you back

- Big picture: surface analysis, winds aloft, convection and icing risk. (Open the Aviation Weather Center; don’t just trust a green app tile.)

- Threats: terrain, crosswind limits, runway condition, NOTAM landmines.

- No-go box: “We do not fly through red returns within X NM of final.”

- Outs: upwind approach, hold fix, alternates with clean weather.

- Triggers: unstable at gate → go-around; vib >2.0 with rumble → QRH and divert.

- Roles: “If weather pops, you fly and talk; I work the box.”

- Words: Script your first radio sentence for the most likely deviation. That removes friction.

If you need a skeleton to copy, you’ll find printable versions and debrief worksheets in Flight School Guides.

Why this sticks: one captain’s closing argument

I remember a night over the Appalachians when a winter warm front turned our “light rain” into moderate chop and a left-engine vib that just wouldn’t settle. We slowed, offset, and asked for a hold over a VMC valley while a squall ate the ILS we’d originally planned. Ten minutes later we shot the crosswind RNAV with a mile of extra straight-in. The jumpseater—a new FO on OE—asked why it felt “weirdly easy.” It wasn’t easy. It was already decided: where we wouldn’t go, what we’d say if weather or an engine asked for a turn, and when we’d go around without a speech. That’s the real job: make the hardest minutes boring.