Introduction: The Solution for Aluminum and Titanium

In our previous guide, we explored Magnetic Particle Inspection, the gold standard for testing steel. But modern aviation is not built on steel; it is built on aluminum, titanium, and magnesium. These non-magnetic materials cannot be tested with magnets. They require a different approach, one based on capillary action. Unlike internal inspections that require a Borescope Inspection Guide, this method finds surface defects on the airframe skin.

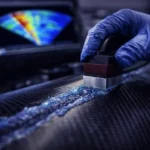

FPI is deceptively simple: coat a part in liquid dye, wash it off, and see where the dye remains trapped in cracks. However, achieving the sensitivity required to find a fatigue crack in a jet engine requires a sophisticated suite of Liquid Penetrant Inspection equipment. From massive multi-stage processing lines to precise electrostatic spray guns, the tools used in FPI are critical for airworthiness.

For the Aviation Maintenance Technician, understanding this equipment is non-negotiable. Whether you are working in a heavy maintenance hangar or an engine overhaul shop, this guide breaks down the tools, tanks, and technologies that define modern FPI.

The “FPI Line”: The Heavy Machinery

In a professional Aircraft MRO facility, you won’t just see a few cans of spray paint. You will see ‘The Line.’ This is a stationary, modular system of stainless steel tanks, rollers, and drying ovens designed to process parts in a strict sequence.

1. The Penetrant Station (The Dip Tank)

The process starts here. This tank holds hundreds of gallons of fluorescent penetrant.

- The Equipment: The tank is usually made of stainless steel to resist corrosion. It features a drainboard and a grill to rest heavy parts.

- Dwell Timers: A critical piece of Liquid Penetrant Inspection equipment is the process timer. Once a part is dipped, it must sit (“dwell”) for a specific time—often 30 minutes—to allow the liquid to seep into microscopic cracks.

- Electrostatic Sprayers: For large parts that cannot be dipped, technicians use electrostatic spray guns. These charge the penetrant mist, ensuring it wraps around the part for 100% coverage with minimal waste.

2. The Emulsifier Station (Method B/D)

This is where the process gets technical. Some penetrants are not water-washable. They require an “emulsifier” (a chemical remover) to make the excess dye rinse away.

- The Tool: This station often looks like a large vat with an automated agitator or bubbler to keep the chemical mix consistent.

3. The Rinse Station (The Wash Bay)

This is the most sensitive step. Wash too little, and the background glows green (noise). Wash too much, and you rinse the dye out of the crack (false negative).

- Control Equipment: This station features calibrated water nozzles. The water pressure is strictly regulated (usually below 40 PSI) and the temperature is thermostatically controlled (typically between 50°F and 100°F).

- UV Background Light: A waterproof UV light is mounted above the wash bay so the technician can see when the background dye is removed.

4. The Drying Oven

Before “developing,” the part must be bone dry.

- The Equipment: An industrial recirculating air oven.

- Calibration: The oven is equipped with digital temperature controllers. It must not exceed 160°F (71°C), or the heat will bake the dye and ruin its fluorescence.

The Consumables: The Chemistry of Detection

Liquid Penetrant Inspection equipment is essentially a delivery system for advanced chemistry. In aviation, we use specific “Sensitivity Levels” defined by AMS 2644.

The Penetrant (Type 1)

Aviation exclusively uses Type 1 (Fluorescent) penetrants. We do not use the visible red dye seen in automotive welding (Type 2) because it lacks the sensitivity to find fatigue cracks.

- Sensitivity Levels:

- Level 2 (Medium): Used for rough castings and airframe fittings.

- Level 3 (High): The standard for most engine parts.

- Level 4 (Ultra-High): Used for critical rotating parts like turbine discs. This liquid is expensive and highly engineered.

The Developer (The Blotter)

Once the part is washed and dried, the dye is trapped inside the crack, but it is invisible. The “Developer” acts like a paper towel, sucking the dye back to the surface to create a “bleed out.”

- Dry Powder (Form a): A fluffy white powder applied in a “Dust Storm” chamber (a cabinet that blows a cloud of powder over the part).

- Non-Aqueous Wet (Form d): An aerosol spray often used in portable kits.

The Inspection Booth: Lighting and Measurement

The final stage of the Liquid Penetrant Inspection equipment ecosystem is the darkroom. This is where the decision is made: Airworthy or Scrap.

1. UV-A LED Lamps

Just like in Magnetic Particle Inspection, the quality of the light determines the quality of the inspection.

- The Standard: Lights must emit UV-A at a peak wavelength of 365nm.

- Intensity: The beam must be strong (minimum 1,000 µW/cm²), but usually, aviation demands much higher intensity (around 5,000 µW/cm²) to make the smallest indications pop.

2. Light Meters (Radiometers)

You cannot guess the light output. Every shift begins with a Radiometer check.

- Dual Function: These handheld tools measure both the UV intensity (to ensure it’s high enough) and the ambient visible light (to ensure the booth is dark enough—less than 2 foot-candles).

3. Inspection Mirrors and Magnifiers

- Magnification: A 10x magnifying loupe is standard gear for an FPI inspector.

- Mirrors: Small dental-style mirrors are used to inspect the internal bores of shafts or the backsides of flanges.

Portable Kits: The “Spot Check”

Not every inspection happens in a tank. If a pilot reports a hard landing and you need to check the landing gear attachment point on the tarmac, you use a Portable FPI Kit.

These kits typically consist of:

- Cleaner/Remover (Solvent): To prep the surface.

- Penetrant (Aerosol): Usually a Level 3 sensitivity dye.

- Developer (Aerosol): A “Non-Aqueous Wet” developer that sprays on as a thin white film.

- Portable UV Light: A battery-operated LED torch.

While convenient, portable kits are messy and less sensitive than a stationary line. They are strictly for localized repairs and cannot replace a full overhaul inspection.

Quality Control: The TAM Panel

How do you know if your penetrant has degraded? Or if your wash water is too hot? You use Process Control monitors.

The TAM Panel (Star Panel)

This is the most famous piece of Liquid Penetrant Inspection equipment. It is a stainless steel panel with five star-shaped cracks of graduated sizes. Every morning, the panel is run through the entire line.

- The Test: If the inspector can see all five stars glowing, the system is a “Go.” If the smallest star is invisible, the system is a “No-Go,” and the chemicals may need to be dumped and replaced.

The NiCr Panel (Twin Panel)

This consists of two identical panels with pre-induced cracks. One is run through your line, and the other is kept as a “master.” Comparing the two ensures your process hasn’t drifted over time.

Safety and Environmental Gear

FPI involves harsh chemicals.

- Contamination Risks: Just like Foreign Object Debris (FOD) can damage an engine, chemical contamination in the penetrant tank can ruin an inspection. Technicians must ensure that no water, dirt, or oil is dragged into the tanks from their clothing or tools.

- Fume Hoods: The developer stations create fine dust, and the penetrant tanks release vapors. Industrial ventilation systems are mandatory to protect the lungs of the Aviation Maintenance Technician.

- Waste Water Treatment: You cannot dump the rinse water down the drain. It contains fluorescent dyes and oils. FPI lines are connected to oil/water separators and carbon filtration systems to ensure environmental compliance.

Conclusion: The Art of Contrast

Liquid Penetrant Inspection equipment is unique in the maintenance world. It combines heavy industrial washing machines with the delicate precision of a photography darkroom. It is a process of chemistry and physics working together to draw a bright green line in the darkness.

For the MRO facility, maintaining this equipment is a constant battle against contamination. Water in the penetrant tank, oil in the developer, or a burnt-out LED on a UV lamp can all cause a missed crack. And in aviation, a missed crack is a risk that cannot be taken. By investing in high-quality tools and adhering to strict daily calibration, the industry ensures that every aluminum wing rib and titanium compressor blade is free of defects and ready for flight.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the difference between Method A and Method D? Method A uses “Water Washable” penetrant—the emulsifier is built into the oil, so you just rinse it off. Method D uses “Post-Emulsified” penetrant. The oil resists water until you dip it in a separate chemical remover. Method D is much more sensitive and is used on critical engine parts.

2. Can I use FPI on steel parts? Yes, FPI works on any non-porous material, including steel, glass, and ceramic. However, for steel, Magnetic Particle Inspection (MPI) is generally preferred because it can detect subsurface cracks that FPI cannot.

3. Why is the developer white? The developer is a white powder that provides a contrasting background. It acts like a whiteboard, making the bright green fluorescent dye bleeding out of the crack stand out vividly for the inspector.

4. How much does an FPI line cost? A full industrial Liquid Penetrant Inspection equipment line (tanks, oven, booth) can cost between $50,000 and $200,000 depending on the size and automation. A simple portable aerosol kit costs around $200.

5. Who certifies FPI equipment? The equipment must meet the standards of ASTM E1417. The penetrant materials themselves are certified to AMS 2644. Routine calibration is required by auditors like the FAA or Nadcap.

6. What is “Over-Washing”? This is the most common error in FPI. If the technician sprays the part with too much water pressure or for too long at the rinse station, they wash the dye out of the crack. This results in a “False Negative,” where a cracked part appears perfectly healthy. This is why water pressure gauges are critical Liquid Penetrant Inspection equipment.