Introduction: The “Graveyard Shift” Superpower

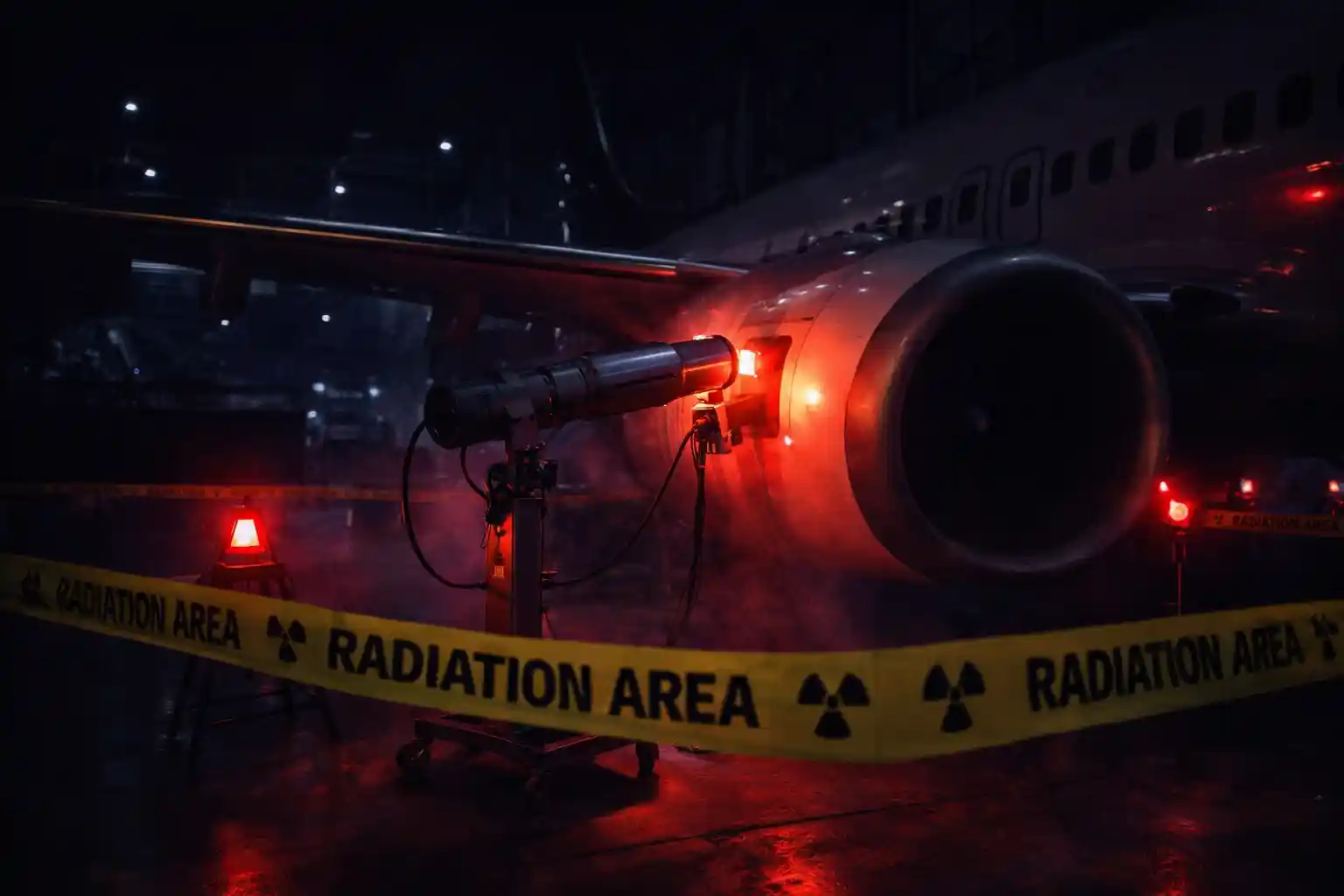

If you walk into a US aircraft hangar at 2:00 AM and see the red strobe lights flashing and yellow “DANGER: RADIATION” tape cordoning off the Boeing 737 tail section, you know the RT crew is at work.

Radiographic Testing (RT) is the “Superman Vision” of aviation maintenance. While Visual Inspection looks at an aircraft and Ultrasonic Testing listens to it, Radiographic Testing is the definitive science of seeing through it. It is the closest practical equivalent to X-ray vision that a technician can command—a powerful perspective that peers into the very heart of a material.

In the high-stakes world of US aviation, under strict FAA oversight, this isn’t just about taking pictures. It’s about mastering the balance between finding microscopic flaws and adhering to Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) safety standards that protect lives both in the air and on the ground.

This comprehensive guide explores the high-precision world of aviation radiography. We will demystify the physics of shadow formation, navigate the critical choice between X-ray and Gamma ray sources, detail the shift from film to Computed Radiography (CR) and Digital Radiography (DR) in Part 145 Repair Stations, and underscore the non-negotiable importance of radiation safety. Whether you’re an aspiring NDT technician or a seasoned mechanic looking to add RT certification to your credentials, this guide provides the foundation you need to understand this critical discipline.

The Core Physics: An Art of Shadows and Densities

At its most fundamental level, Radiographic Testing is the capture of radiation shadows. The process hinges on the differential absorption of penetrating radiation as it travels through materials of varying density. Understanding this principle is essential to interpreting radiographic images accurately and recognizing the defects that could compromise aircraft safety.

The Radiographic Chain: From Source to Image

Every radiograph follows a predictable sequence that transforms invisible radiation into visible evidence of internal flaws:

The Radiation Source: A device generates high-energy electromagnetic radiation. In US industrial settings, this is either an X-ray generator tube or a sealed radioactive isotope that emits Gamma rays, most commonly Iridium-192 or Selenium-75.

Penetration & Travel: This directed beam passes through the aircraft component under inspection, whether it’s a turbine blade, wing spar, or fuselage section. The radiation travels in straight lines from the source through the object.

Differential Absorption: Here’s where the magic happens. As radiation encounters different materials and thicknesses:

- High-Density Areas (such as a steel spar cap, thick weld, or solid aluminum structure) absorb more radiation, preventing it from reaching the detector.

- Low-Density Areas (including aluminum skin, an air pocket, corrosion cavities, or cracks) allow more radiation to pass through with minimal absorption.

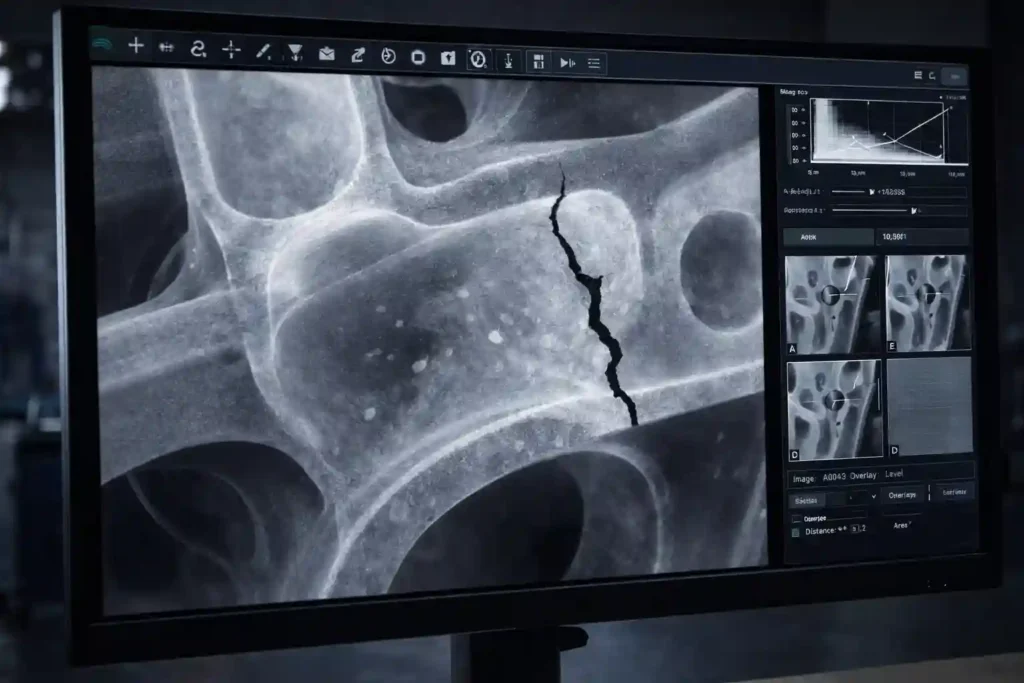

The Final Radiograph: The radiation that successfully penetrates the component strikes a detection medium—film, a phosphor plate, or a digital detector array—creating the final image. Understanding how to read this image is crucial:

- Areas that absorbed little radiation (cracks, voids, porosity) appear DARKER on the image because more radiation reached the detector.

- Areas that absorbed substantial radiation (dense metal, thick sections) appear LIGHTER because less radiation penetrated through.

The “Negative” Rule: Remember, a radiograph functions like a photographic negative. A crack is essentially empty space, so it allows more radiation to reach the film or detector, resulting in a dark line against the lighter background of solid metal. This counterintuitive relationship confuses beginners but becomes second nature with experience.

The beauty of radiography lies in its simplicity: shadows reveal secrets. A skilled radiographer learns to recognize the subtle gradations of gray that indicate everything from water intrusion in honeycomb structures to microscopic cracks in critical welds.

Source Selection: X-Rays vs. Gamma Rays

In aviation NDT, choosing between an X-ray generator and a Gamma ray source is a tactical decision based on the inspection location, material thickness, required image quality, and practical considerations like power availability. Both technologies have distinct advantages and limitations that make them suited for different scenarios.

X-Ray Generators: The Hangar Standard

X-ray generators are electrically powered machines where high-voltage electrons are accelerated and slammed into a tungsten target, producing X-rays through a process called Bremsstrahlung radiation. These sophisticated devices have become the workhorse of shop-based aviation inspections.

Advantages:

Safety Control: The beam is only produced when the machine is powered on and activated. Turning off the switch immediately stops all radiation emission, providing superior safety control compared to always-active isotopic sources.

Adjustable Energy: Variable voltage (kV) and current (mA) settings allow technicians to fine-tune the radiation energy and intensity for optimal contrast on different materials and thicknesses—from delicate avionics housings to robust fuel valves.

Superior Image Quality: Generally produces sharper images with better contrast resolution than Gamma sources, particularly on thin to medium-thickness components.

No Decay: Unlike radioactive isotopes, X-ray tubes don’t lose strength over time, providing consistent performance throughout their operational life.

Disadvantages:

Power Dependency: Requires a heavy power supply and cables, limiting portability and making field inspections challenging.

Size and Weight: The equipment is bulky and often requires dedicated carts or installation, making it impractical for on-aircraft work or confined spaces.

Cooling Requirements: Continuous operation generates substantial heat, requiring cooling systems and duty cycle management.

Best Applications: Shop environments, component overhaul facilities, MRO (Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul) operations, and any inspection where power is readily available and superior image quality is paramount.

Gamma Ray Sources: The Portable Powerhouse

Gamma ray systems use small, permanently radioactive pellets (isotopes) housed within heavily shielded exposure devices, often called “cameras” or “crawlers.” The American Society for Nondestructive Testing (ASNT) provides comprehensive safety guidelines for operating these powerful but potentially hazardous devices.

Advantages:

Extreme Portability & Independence: No power cords, generators, or electrical infrastructure needed. The camera is compact enough to be positioned in confined spaces like wing boxes, carried up scissor lifts to vertical stabilizers, or used in remote field locations where aircraft are grounded.

Deep Penetration: Gamma rays from isotopes like Iridium-192 possess exceptional penetrating power, making them ideal for thick steel parts, titanium components, and dense structural elements that would require impractically high X-ray energies.

Constant Energy Output: The isotope emits at a fixed, predictable energy level, simplifying exposure calculations once you know the material type and thickness.

Rugged Reliability: No electronic components to fail, no tubes to burn out. These devices withstand harsh environmental conditions that would disable X-ray generators.

Disadvantages:

Inherent Radiation Hazard: The source is always emitting radiation. It cannot be “turned off,” only shielded by moving the pellet into a safe position within its protective housing using a drive cable mechanism. This demands rigorous handling protocols and creates a constant safety concern.

Regulatory Complexity: Operating Gamma sources requires extensive Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) licensing, regular leak testing, security protocols, and documentation that significantly exceeds X-ray requirements.

Isotope Decay: Radioactive sources lose strength over time according to their half-life. Iridium-192, the most common aviation isotope, has a half-life of 74 days, requiring replacement approximately every six months to maintain practical exposure times.

Image Quality Limitations: Generally produces slightly less sharp images than X-rays due to the physical size of the source and the fixed energy spectrum.

Best Applications: Field work, on-aircraft inspections, checking wing spar caps, large fuselage welds, control surface attachments, engine mounts, and any situation where the component cannot be easily removed or where portability is essential.

Making the Choice

The decision between X-ray and Gamma often comes down to practical considerations. If you’re in a shop with good power and inspecting removable components, X-ray provides superior image quality and safety control. If you’re standing on a scissor lift inspecting a 737 horizontal stabilizer attachment at midnight on a remote tarmac, that Iridium-192 camera is your only realistic option.

Many large MRO facilities and airlines maintain both capabilities, selecting the appropriate technology for each specific inspection scenario. Understanding the strengths and limitations of each system is essential for any serious RT technician.

The Digital Revolution: From Film to Real-Time Imaging

The radiographic imaging landscape has undergone a transformative shift over the past two decades, moving from analog chemistry to digital efficiency. This evolution has fundamentally changed how aviation inspections are conducted, documented, and analyzed.

Traditional Film Radiography: The Analog Benchmark

Process: A flexible film coated with a silver-halide emulsion is placed behind the component being inspected. After exposure to radiation, the film is chemically processed in a darkroom using developer and fixer solutions, producing a permanent analog image that’s viewed on a backlit lightbox.

Advantages:

- Excellent inherent spatial resolution capable of revealing extremely fine details

- Creates a permanent, stable archival record that doesn’t depend on digital storage systems

- Well-established acceptance criteria and interpretation standards refined over decades

Disadvantages:

- Chemical processing is time-consuming, typically requiring 30-45 minutes from exposure to interpretation

- Environmental concerns regarding chemical disposal and darkroom waste

- Film is a consumable cost that adds up quickly in high-volume operations

- Images cannot be easily enhanced, measured digitally, or shared electronically

- Storage of physical films requires significant space and climate control

Status in 2026: While still specified for certain high-resolution applications and maintained as a backup capability in some facilities, traditional film radiography is rapidly declining. Regulatory acceptance of digital methods and environmental pressures have accelerated this transition.

Computed Radiography (CR): The Transitional Powerhouse

Computed Radiography represents the bridge between traditional film and fully digital systems, offering many digital advantages while maintaining workflow compatibility with film-based processes.

Process: Instead of film, CR uses flexible, reusable Phosphor Imaging Plates (IP) that look similar to X-ray film cassettes. When exposed to radiation, the phosphor crystals in the plate store energy as a latent image. The plate is then inserted into a dedicated laser scanner (reader), which releases the stored energy as light. This light is detected by photomultiplier tubes and converted into a high-resolution digital image file that can be viewed, enhanced, and stored on computer systems.

Benefits:

Reusability: Imaging plates can be erased and reused thousands of times, eliminating film and chemical costs while reducing environmental impact.

Exceptional Dynamic Range: CR offers significantly greater exposure latitude than film, meaning slight over- or under-exposure doesn’t ruin the image. This forgiveness reduces retakes and improves productivity.

Digital Workflow: Images can be enhanced using software (adjusting contrast, brightness, edge enhancement), measured precisely, annotated digitally, and easily archived in PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication Systems).

Portability: The imaging plates are as portable as film cassettes, making CR ideal for field inspections where you want digital benefits without the rigidity of DR panels.

Cost-Effectiveness: Lower operating costs than film and significantly less expensive equipment investment than DR systems.

Aviation Applications: Extremely popular in MRO environments for its balance of portability, image quality, and cost-effectiveness. Perfect for inspecting the wide variety of part sizes and shapes encountered in aircraft maintenance—from small turbine blades to large structural components. According to industry surveys, CR remains the most common digital radiography method in aviation maintenance facilities as of 2026.

Digital Radiography (DR) & Digital Detector Arrays (DDA): The Instant Future

Digital Radiography represents the cutting edge of radiographic technology, eliminating all intermediate processing steps to provide truly real-time imaging.

Process: DR employs fixed, rigid flat-panel detectors containing pixelated arrays of sensors (typically amorphous silicon or amorphous selenium). These detectors convert X-ray or Gamma ray energy directly into electrical signals through either direct conversion (photoconductors) or indirect conversion (scintillators plus photodiodes). The digital signal is instantly transmitted to a computer for display and analysis.

Benefits:

Real-Time Imaging: See images appear on a monitor within seconds of exposure, enabling immediate technique adjustment, part repositioning, and rapid decision-making. This transforms radiography from a batch process to an interactive inspection.

Maximum Throughput: No processing delay, no scanning step, no darkroom time. This dramatically increases inspection speed, making DR ideal for production environments and time-critical maintenance situations.

Consistent Image Quality: Digital detectors provide predictable, reproducible results without the variables introduced by chemical processing or plate reader calibration.

Advanced Analytics: Seamless integration with Automated Defect Recognition (ADR) software that can flag potential indications, digital archiving systems, and sophisticated measurement and analysis tools.

Radiation Dose Efficiency: DR systems typically require 50-70% less radiation exposure than film for equivalent image quality, improving safety and extending isotope life.

Aviation Applications: The gold standard in high-volume manufacturing (such as turbine blade and casting inspection lines) and increasingly adopted in advanced MRO facilities for critical, time-sensitive inspections. Organizations like Boeing have invested heavily in DR technology for production quality control.

Limitations:

- High capital cost (panels can range from $50,000 to $200,000)

- Rigid panels are less versatile than flexible CR plates for oddly-shaped parts

- Detector fragility requires careful handling

- Limited detector sizes may require multiple exposures for large components

The Digital Shift in Practice

The transition from film to digital has been gradual but inexorable. While some organizations jumped directly from film to DR, most followed a staged approach: film → CR → DR, with many facilities currently operating CR systems and evaluating DR for specific applications.

The choice between CR and DR often comes down to volume and application. For general-purpose MRO work with varied part sizes and moderate volume, CR’s flexibility and lower cost make it attractive. For high-volume, repetitive inspections of similar parts (like daily turbine blade production), DR’s speed and automation justify the investment.

Regardless of the technology, the fundamental physics remain unchanged. The radiation still creates shadows, the technician still must understand exposure calculations, and the interpreter still needs the trained eye to distinguish defects from artifacts. The digital revolution has made radiography faster, more efficient, and environmentally friendlier—but it hasn’t made it easier. If anything, the sophistication of modern imaging demands even greater expertise from today’s RT technicians.

Radiation Safety: The ALARA Imperative

Radiographic Testing is the only major NDT discipline that presents an inherent, potentially lethal hazard to technicians and bystanders through ionizing radiation exposure. This isn’t hyperbole or cautionary exaggeration—improper RT practices have resulted in severe radiation injuries and fatalities worldwide. Safety is not merely a guideline or best practice; it is the absolute, non-negotiable bedrock of responsible radiographic work.

The governing principle is ALARA: As Low As Reasonably Achievable. This philosophy recognizes that while some radiation exposure is inevitable in RT work, every exposure must be justified, optimized, and minimized through careful planning and execution.

The Three Cardinal Rules of Radiation Safety

These fundamental principles, often called the “radiation safety trinity,” provide the framework for all RT safety protocols:

1. TIME: Minimize Exposure Duration

- Radiation dose is directly proportional to exposure time

- Plan every shot meticulously before approaching the source

- Use exposure calculators and charts to determine exact timing

- Never linger in radiation areas; complete necessary tasks efficiently and exit immediately

- For Gamma sources, practice manipulating the drive cable and exposure device until you can work smoothly without hesitation

2. DISTANCE: Maximize Separation from Source

- Radiation intensity follows the Inverse Square Law: doubling your distance from the source reduces your exposure to one-quarter; tripling the distance reduces it to one-ninth

- For Gamma radiography, use the longest practical guide tubes to position the source remotely

- Never approach closer to an active source than absolutely necessary

- During X-ray operations, maximize distance from the tube head using remote triggering systems

- Remember: a few extra feet of distance can reduce your dose by 90% or more

3. SHIELDING: Employ Appropriate Barriers

- Lead, concrete, steel, and even water are effective radiation shields

- Fixed barriers (walls, protective enclosures) are always preferable to personal protective equipment

- Lead aprons and thyroid collars provide some protection but should never replace distance and time controls

- When selecting a radiography location, consider natural shielding (building walls, earth berms, equipment) to reduce controlled area size

- For permanent installations, engineer proper shielding into the facility design

Operational Safety Protocols in Aviation

Beyond the three cardinal rules, specific protocols govern every radiographic operation in US aviation settings:

Radiation Controlled Area Establishment:

- A clearly defined controlled area must be established and physically barricaded before every exposure

- The boundary is set at the distance where radiation levels drop to 2 millirem per hour (mR/hr) or the regulatory limit for the specific operation

- Post “CAUTION: RADIATION AREA” or “DANGER: RADIATION AREA” signs at all entry points

- For aircraft inspections, this often means evacuating entire sections of a hangar or establishing large outdoor perimeters

Radiation Survey Requirements:

- A certified Radiation Safety Officer (RSO) or qualified Level II RT technician must conduct a complete 360-degree survey with a calibrated radiation survey meter before declaring an area safe

- Survey during source exposure at multiple points around the perimeter to verify the controlled area boundary

- Survey again after source is secured to confirm radiation levels have returned to background

- Document all survey results as part of the exposure record

Personnel Monitoring:

- All RT personnel must wear personal dosimeters (typically Thermoluminescent Dosimeter badges) to track cumulative radiation exposure

- Dosimeters must be worn on the body, typically at chest level, to represent whole-body dose

- Dosimeters are analyzed monthly or quarterly by licensed services

- Results must remain well below regulatory limits (currently 5,000 millirem per year for occupational exposure, with many companies enforcing much lower administrative limits)

- Any unusual readings trigger immediate investigation

Source Security and Accountability:

- Gamma sources must be secured when not in use, typically in locked, shielded storage containers

- A chain-of-custody log must document every movement and use of radioactive sources

- Regular leak tests (every six months for most isotopes) verify source capsule integrity

- Annual audits ensure all sources are accounted for and properly licensed

Training and Certification:

- All RT technicians must complete NRC-approved radiation safety training

- Regular refresher training (typically annual) maintains competency

- Emergency response procedures must be practiced, including source disconnect procedures and radiological incident response

The Human Factor: Why Safety Culture Matters

Technical protocols and regulations provide the framework, but safety ultimately depends on human decision-making. The pressure to complete inspections quickly, meet production schedules, or avoid the hassle of establishing proper controlled areas has led to tragic incidents.

Consider the radiographer who thinks, “It’s just one quick shot—I’ll skip the full survey this time.” Or the supervisor who pressures the RT crew to work faster, implicitly encouraging shortcuts. These seemingly minor decisions can have catastrophic consequences.

The most successful RT programs cultivate a culture where safety is genuinely valued, not just procedurally mandated. This means:

- Empowering any team member to stop work if they observe unsafe conditions

- Never penalizing technicians for taking the time to do things right

- Treating near-misses as learning opportunities, not disciplinary events

- Leadership actively demonstrating commitment to ALARA principles

Regulatory Oversight

RT operations in US aviation fall under dual regulatory oversight:

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC): Governs all aspects of radioactive source acquisition, use, storage, transfer, and disposal. Violations can result in license revocation, substantial fines, and even criminal prosecution.

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA): Governs the technical adequacy of NDT procedures and the qualifications of personnel performing inspections on aircraft and components. Requires that RT procedures comply with both NRC safety regulations and aviation quality standards.

This dual oversight means RT technicians must satisfy both safety regulators and aviation authorities—a demanding but necessary requirement that ensures both worker protection and airworthiness.

Key Applications in Modern Aviation Maintenance & Manufacturing

Radiography excels at solving specific, critical problems that other NDT methods cannot adequately address. Understanding when and why to specify RT is essential for effective inspection planning.

1. Detection of Water Ingress in Composite Honeycomb Structures

The Problem: Modern aircraft extensively use composite sandwich structures—typically carbon fiber or fiberglass skins bonded to lightweight Nomex or aluminum honeycomb cores—in control surfaces (ailerons, flaps, rudders, elevators), fairings, interior panels, and some secondary structures. These assemblies are strong, light, and aerodynamically efficient, but they have an Achilles’ heel: water intrusion.

If sealant fails at panel edges, fastener holes, or skin damage sites, moisture can enter the honeycomb core. At ground level, this causes gradual degradation. At altitude, the water freezes, expands by approximately 9% in volume, and generates tremendous internal pressure. This expansion can delaminate the skin from the core, create pillow-like bulges visible on the aircraft surface, and ultimately lead to catastrophic structural failure of the control surface.

The RT Solution: Radiography provides a fast, reliable method to detect trapped moisture. An X-ray exposure clearly reveals water presence as a diffuse, foggy, or “cloud-like” darker area within the regular hexagonal pattern of the dry honeycomb cells. Water, being denser than air, absorbs less radiation than the empty cells, appearing darker on the image. Moisture typically pools at the bottom of the component due to gravity, creating characteristic patterns.

Practical Application: During routine maintenance checks, suspect panels (identified by unusual weight during tap testing or panel removal) are radiographed. The RT image shows not only the presence of water but its distribution pattern, helping technicians determine if the panel can be dried and resealed or requires replacement. This non-invasive inspection preserves the panel’s integrity while providing definitive evidence of moisture damage.

2. Internal Quality Assessment of Castings

The Problem: Critical aircraft components—including engine accessory gearboxes, hydraulic pump housings, valve bodies, landing gear components, and structural fittings—are frequently manufactured through casting processes using aluminum, magnesium, or specialized alloys. Casting inherently risks internal defects: gas porosity (trapped air bubbles), shrinkage cavities (voids from inadequate metal feed during solidification), non-metallic inclusions (slag or oxide particles), and hot tears (cracks formed during cooling).

These volumetric defects create stress concentration points that can initiate catastrophic failures under operational loads. External visual inspection cannot detect these internal flaws, and many castings have complex geometries that make ultrasonic inspection difficult or impossible.

The RT Solution: Radiography provides a comprehensive volumetric map of the casting’s internal soundness. Different defect types produce characteristic radiographic signatures:

- Gas Porosity: Appears as scattered, round, dark indications of varying sizes distributed through the casting

- Shrinkage Cavities: Show as irregular, sometimes dendritic (tree-branch-shaped) dark areas, often near section transitions

- Non-Metallic Inclusions: Appear as dark, irregular shapes with varying opacity depending on inclusion density

- Cracks: Manifest as sharp, linear dark indications, though orientation matters significantly

Practical Application: In manufacturing, 100% radiographic inspection of critical castings is common. Each casting is shot from multiple angles to ensure complete coverage. Images are evaluated against acceptance criteria defined in specifications like AMS-STD-2175 (castings for aerospace applications). Rejected castings are scrapped or, if economically justified, subjected to repair procedures followed by re-inspection.

3. Verification of Weld Integrity

The Problem: Welded joints are ubiquitous in aircraft structures—engine mounts, hydraulic reservoirs, fuel tanks, high-pressure air ducts, firewall assemblies, and exhaust systems all rely on weld quality. Weld defects compromise strength and can lead to leaks, fires, or structural failures. Common weld discontinuities include:

- Lack of Fusion: Incomplete bonding between weld metal and base metal or between weld passes

- Lack of Penetration: Weld metal fails to penetrate through the joint thickness

- Porosity: Gas bubbles trapped in solidifying weld metal

- Cracks: Can be hot cracks (formed during solidification) or cold cracks (formed after cooling)

- Tungsten Inclusions: Dense tungsten particles from contaminated TIG welding electrodes embedded in weld metal

- Slag Inclusions: Non-metallic oxides or flux trapped in the weld

The RT Solution: A properly executed weld radiograph reveals the internal profile and soundness of the weld bead. Key features and their radiographic appearance:

- Lack of Fusion: Appears as dark, elongated linear indications along the weld edge or between passes, often with well-defined straight edges

- Porosity: Shows as scattered small, round, dark circles distributed through the weld bead

- Cracks: Manifest as sharp, often jagged dark lines that may branch

- Tungsten Inclusions: Being much denser than steel or aluminum, appear as distinct, bright white spots that stand out prominently

- Proper Penetration: Visible as consistent weld bead profile through the joint thickness

Practical Application: Weld radiography is mandatory for many critical aircraft welds per FAA regulations and manufacturer specifications. Technicians position the radiation source and detector to achieve optimal viewing of the weld profile, often using specialized techniques like double-wall, single-image (DWSI) or double-wall, double-image (DWDI) for pipe welds. Image Quality Indicators (IQIs, also called penetrameters) placed on or near the weld verify that the radiographic technique achieves required sensitivity.

4. Corrosion and Thickness Loss Detection

The Problem: Hidden corrosion in aircraft structures—particularly in fuselage lap joints, doubler plates, structural reinforcements, and internal pipe walls—represents a insidious threat. External surfaces may appear pristine while underlying corrosion reduces material thickness, weakening the structure and creating risk of sudden failure.

Exfoliation corrosion (layer-by-layer material loss) and pitting corrosion (localized deep attacks) are particularly dangerous because they progress internally with minimal external evidence until substantial damage has occurred.

The RT Solution: While radiography is not a precision thickness gauge like ultrasonic testing, it can reveal corrosion patterns through several mechanisms:

- Reduced Density: Corroded areas, having lost material or containing corrosion products less dense than base metal, allow more radiation to pass through, appearing darker on radiographs

- Pattern Recognition: Characteristic corrosion patterns (uniform thinning, pitting clusters, exfoliation layers) create recognizable radiographic signatures

- Comparative Analysis: Comparing radiographs of similar structures in corroded versus non-corroded areas highlights abnormalities

Practical Application: RT serves as an effective screening tool for hidden corrosion, particularly in multi-layer assemblies where access for other methods is limited. When RT reveals suspected corrosion, follow-up with ultrasonic thickness gauging provides quantitative measurements for engineering assessment. This two-step approach—RT for detection and location, UT for quantification—optimizes inspection efficiency.

5. Foreign Object Detection

Aircraft maintenance occasionally requires verification that critical areas are free of foreign objects—tools, fasteners, wire fragments, or other debris that could cause catastrophic damage. Radiography can reveal metallic and dense non-metallic objects inside sealed cavities, composite structures, or assembled components where direct visual inspection is impossible.

Advantages, Limitations, and the Technician’s Role

Understanding the capabilities and constraints of radiographic testing allows you to apply it effectively and recognize when alternative or complementary methods are needed.

Advantages of Radiographic Testing

Volumetric Inspection Capability: RT’s unique ability to examine the internal structure of components provides comprehensive integrity assessment that surface methods cannot match. You’re not just checking for surface-breaking defects—you’re seeing through the entire volume.

Permanent, Objective Record: The radiograph, whether film or digital file, serves as an unalterable record of the component’s condition at the time of inspection. This documentation proves invaluable for quality records, legal proceedings, engineering analysis, and historical trending. Unlike real-time methods that depend on technician notes and memory, the image can be reviewed by multiple experts independently.

Intuitive Visual Result: The shadow-based image is generally easier for engineers, quality managers, and non-NDT personnel to understand compared to A-scans (UT), impedance plane displays (ET), or magnetic particle patterns. This accessibility facilitates communication between inspection personnel and decision-makers.

Wide Material Applicability: RT effectively inspects metals, composites, ceramics, plastics, and multi-material assemblies. Few NDT methods offer such versatility.

Detects Both Surface and Subsurface Defects: Unlike penetrant testing (PT) or magnetic particle inspection (MPI) that only find surface-connected discontinuities, RT reveals defects regardless of their depth within the material.

Inherent Limitations

Radiation Hazard & Regulatory Burden: The safety infrastructure, specialized licensing, area evacuation requirements, and regulatory oversight create operational complexity and cost that other NDT methods don’t face. RT operations can disrupt adjacent work activities and limit when and where inspections can occur.

Orientation Sensitivity: Like MPI, radiography is most sensitive to discontinuities aligned parallel to the radiation beam path. A tight, laminar crack oriented perpendicular to the beam may show minimal contrast and remain undetected because the radiation passes through very little void space. This geometric limitation requires careful technique planning and often multiple shot angles.

Two-Dimensional Superimposition: A single radiograph compresses a three-dimensional object into a two-dimensional image. Defects at different depths through the material thickness appear superimposed, potentially making interpretation challenging. Complex geometries, overlapping structures, or multiple defects aligned with the beam can create confusing images. Advanced techniques like stereoscopic radiography or computed tomography (CT scanning) provide depth discrimination but add significant complexity and cost.

Capital and Operational Investment: High-quality RT equipment, particularly DR systems, represents substantial capital investment ($100,000 to $500,000+ for complete systems). Ongoing costs include source replacement (for Gamma), detector maintenance, dosimetry services, radiation safety programs, and regulatory compliance activities.

Thickness Limitations: Very thin materials may not provide sufficient contrast, while extremely thick or dense materials may require impractically high radiation energies or prohibitively long exposure times.

Not Real-Time for Film/CR: Despite digital advances, film and CR still involve processing delays between exposure and image availability, though DR provides true real-time imaging.

The Modern RT Technician: A Tri-Skilled Expert

Mastering Radiographic Testing in 2026 demands a unique blend of competencies that extends far beyond simply “taking X-rays.” The professional RT technician must develop three distinct skill sets:

1. The Physicist: Deep understanding of radiation physics, interaction mechanisms, geometric principles (unsharpness, magnification, distortion), exposure calculations, inverse square law applications, and the technical specifications of radiation sources and detection systems. You must know why certain techniques work and be able to calculate proper exposure parameters for unfamiliar scenarios.

2. The Safety Officer: Unwavering commitment to ALARA principles, comprehensive knowledge of NRC and state regulations, dedication to protecting yourself and others from radiation hazards, and the moral courage to refuse unsafe practices regardless of production pressure. Your radiation safety knowledge, reinforced by resources from organizations like ASNT, must be absolute and non-negotiable.

3. The Analytical Interpreter: Development of the skilled eye to distinguish between relevant defects, part geometry variations, and innocuous image artifacts in complex radiographs. This skill comes primarily through experience and mentorship, learning to recognize subtle patterns that indicate real problems versus normal variations or imaging anomalies.

Beyond these core competencies, successful RT technicians possess strong communication skills (explaining findings to engineers and managers), meticulous documentation habits (maintaining legally defensible records), mechanical aptitude (positioning equipment and parts), and continuous learning mindset (staying current with evolving technology and standards).

Your Signature is Your Bond: The Reality of Liability

In the US aviation sector, RT isn’t just about finding defects—it’s about managing professional and legal liability. Whether you’re radiographing a Boeing 737 rudder attachment at a Part 145 Repair Station or inspecting a general aviation spar reinforcement in the field, both the FAA and NRC maintain zero tolerance for shortcuts or compliance failures.

When you interpret that radiograph and sign the inspection report, you aren’t simply looking at shadows—you are placing your name, certification number, and professional reputation on record, certifying that component meets airworthiness standards. This signature carries legal weight. If that component later fails and investigation reveals you missed a detectable defect or violated procedure, you face potential certificate revocation, civil liability, and in cases of gross negligence, even criminal prosecution.

The liability extends to safety compliance as well. If your controlled area boundary isn’t properly established at the 2 mR/hr regulatory limit, or if you sign off an inspection without verifying the Image Quality Indicator (IQI) demonstrates required sensitivity, you’re not just risking an NRC violation notice—you’re jeopardizing your career and potentially endangering lives.

This reality demands absolute professionalism: follow procedures exactly as written, document everything thoroughly, never succumb to pressure to cut corners, and maintain the integrity of your certification through ethical practice. The aircraft-flying public depends on your competence and honesty. Your professional future depends on maintaining that trust.

Conclusion: The Revealing Light Ensuring Structural Transparency

Radiographic Testing endures as one of the most powerful, respected, and demanding specialties within aviation NDT. It provides the irreplaceable service of making the invisible visible, revealing the hidden flaws that lurk within critical structures where they could otherwise remain undetected until catastrophic failure occurs.

As the industry accelerates into the digital age with real-time digital detector arrays, automated defect recognition software, and even portable CT scanners, the tools are becoming faster, smarter, and more capable. Yet the core mission remains unchanged and vital: to act as the definitive check on internal integrity, to provide the transparency needed for absolute confidence in structural soundness, and to ensure that every aircraft component is not just superficially acceptable, but structurally perfect from the inside out.

The radiographer’s careful work—guided by physics, governed by safety, and validated through rigorous training—continues to be a fundamental pillar of flight safety in the modern aerospace era. Whether you’re an aspiring NDT technician considering RT specialization or an experienced mechanic looking to expand your capabilities, the field offers challenging, respected work that directly contributes to aviation safety.

For those ready to pursue advanced NDT certifications and career development in aviation maintenance, explore the comprehensive resources available through Aviation Titans’ Career & Training section. Understanding the full spectrum of inspection technologies—from visual methods to advanced radiography—positions you for success in this demanding but rewarding field.

The future of aviation safety depends on skilled professionals who can wield the “X-ray vision” of radiographic testing with technical excellence and unwavering commitment to safety. If you’re ready to see beyond the surface and master one of aviation’s most critical inspection disciplines, the radiographic testing specialty awaits. For expert guidance on your NDT career path, connect with Aviation Titans to access industry insights and professional development resources.

The invisible threats to aircraft structural integrity need not remain hidden. Through the revealing light of radiographic testing, we ensure transparency, confidence, and safety for every flight.